The International Campaign for Real History

There have been hundreds of horrific Stories from the Gas Chambers of Auschwitz and other Nazi camps. We see here how uncritically they are seized upon by Robert Jan Van Pelt who has the chutzpah to say that they contain no improbable allegations: now click for the unabridged version of his source

|

|||

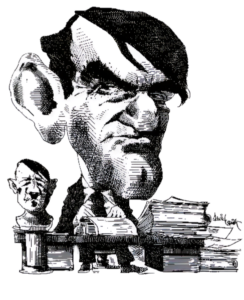

Eminent Dutch author of Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present (Yale University Press)

|

From Robert Jan Van Pelt, The Case for Auschwitz, Evidence from the Irving Trial (Indiana University Press), pages 167-169.

The name “Auschwitz” turned up again and again. Members of the British Parliament, who had visited Buchenwald by invitation of General Eisenhower, were quoted in The Times of April 28 as saying that many prisoners told them that conditions in other camps, particularly those in Eastern Europe, were far worse than at Buchenwald. “The worst camp of all was said by many to be at Auschwitz; these men all insisted on showing us their Auschwitz camp numbers, tattooed in blue on their left forearms.”105 As the British Members of Parliament drafted their report, a special intelligence team of the Psychological Warfare Division of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces, headed by Lieutenant Albert G. Rosenberg, questioned former inmates in an effort to document the atrocities. They were assisted by a group of prisoners, headed by Austrian journalist and economist Dr. Eugen Kogon — the same Kogon who was to become the focus of Stäglich‘s scorn thirty years later. The team interviewed some 150 people and in the process gathered a number of important testimonies about Auschwitz and other extermination camps in the East. It is important to note that at the time that Rosenberg, Kogon, and their colleagues took these testimonies, the Soviet commission had not yet published its results. One of the witnesses was 15-year-old Janda Weiss, who had been deported to Birkenau a year earlier with a transport of 1,500 Jews from Theresienstadt. He was one of the 98 people of the family camp who was spared when the Theresienstadt Jews were gassed. As a kitchen helper, he visited the barracks where the Sonderkommandos were housed. “These comrades told me about the horrors of the crematorium, where I would later work.”

Intentional Evidence • 167

|

Kogon was to refer to Weiss’s testimony in his book. As Kogon had never been in Auschwitz, Stäglich felt free, as we have seen at the beginning of this chapter, to reject Weiss’s testimony. But when we consider the evidentiary value of Weiss’s statement following Stäglich’s hermeneutical rules, we must conclude that it should be taken seriously. He made specific allegations and he provided specific details, such as the name of the man in charge of the crematoria (Moll) and details of the undressing room and the gassing apparatus. Weiss’s testimony did not contain contradictions, nor did it contain improbable allegations.107 German Jew Walter Blass testified that Jews were subjected to selection on other occasions after their arrival. This procedure was a regular occurrence for those imprisoned in the camp. “Selections occurred at irregular intervals, sometimes after two or three months, then after four to five months, then again, as in January 1944, twice within two weeks.” At such a selection, “Jews had to undress completely and were quickly observed front to rear. Then, according to whim, they were sent to the right to record the prisoner number tattooed on the arm; that meant the death sentence. Or they were sent to the left, that is, back to the barracks; that meant a prolongation of life.” Those who were sent to the right were locked in specially guarded barracks. “Often they remained there for two to three days, usually without food, since they were already considered to be ‘disposed of.”‘108 The interest in the camps generated by Belsen and Buchenwald and the various references appearing in the Western press to Auschwitz offered the Polish government-in-exile a good opportunity to present the atrocities of Auschwitz to the Western public. The first substantial report to appear after the liberation of Auschwitz was entitled “Polish Women in German Concentration Camps,” and it was published in the May 1, 1945, issue of the Polish Fortnightly Review. The article consisted of two eyewitness testimonies, some statistics, and a note on medical experiments in the women’s camp. The first testimony was entitled “An Eyewitnesses’s Account of the Women’s Camp at Oswiecim-Brzezmnyka (Birkenau) — Autumn, 1943, to Spring, 1944,” and like all the other articles published in the Polish Fortnightly Review, it was anonymous. It is, however, clear that it was written shortly after the beginning of the Hungarian Action. The

168 • The Case for Auschwitz

Footnotes:

|

|

David Irving notes:

|

|