The International Campaign for Real History

|

|

IN 1962 I had just finished writing a series of 37 articles on the bombing war, “Wie Deutschlands Städte Starben,” for the German weekly magazine Neue Illustrierte (Cologne); the editors asked me to cast around for a suitable naval theme for a sequel, and my eye lighted upon an article by Captain Stephen Roskill, the official historian, in The Sunday Telegraph highlighting the disastrous 1942 Arctic convoy PQ.17. It seemed that of some 38 ships that sailed, nearly all were sunk, and each had gone their separate way after the convoy was scattered on July 4, 1942 in the mistaken belief that Tirpitz, the German battleship, was just about to attack.

It is a story of invididual heroism by members of an unsung breed of brave men, the sailors of the British and American merchant navies. Their ships were virtually unarmed, and often carried highly explosive cargoes. The classic dynamite-cargo film La salaire du peur has nothing to the tension that rises in these pages. I knew many of the seamen too, and working on the electronic version I found it impossible not to get involved in their stories all over again. In my diary I wrote a few days ago: I continue at ten p.m. with the preparation of The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17 for the Internet and a new print edition. I find myself reading it, and tears of pride and something else coming welling into my eyes as I cannot stop turning the pages: the story of the Hartlebury, the courage of the crew of the rescue ship Zamalek — the sinister wording, as the U-334 comes purring out of the mist, the icy water cascading off her conning tower, to inspect the damage she has done. The individual tales of suffering and heroism, all come flooding back to me now. I wish I could write as well now as I did then, aged still only twenty-five! I wallow in the Englishness of it all, and in the Royal Navy that my father served.It seems like only yesterday that he and I sat in the front room in Elgin Avenue, him gruffly pointing out the wrong Navalese, the faulty terms, the ranks and signals and jargon of it all, before he lumbered back with his heavy paunch — the undetected cancer already rebelling within — and rolling gait to the polished table on which he was slowly and painfully putting the final touches to his own last book, The Smokescreen of Jutland. he was a junior officer in that famous 1916 battle, the last great clash of entire battle fleets. He drafted the manuscript in handwriting, and dictated it onto tape; and I typed it up for him each afternoon, cursing at the facility with which this old sea dog commanded the English tongue, while I had to hunt and chew and polish and chisel at each damned sentence of PQ.17 before I committed it to paper. After I fell out with my first publisher William Kimber (he paid me only £67 for my translation of a whole book,

The book was the victim of a celebrated libel action, fought in the High Court in London in 1970, and withdrawn from sale and libraries in consequence. While it was still vividly before me, I wrote a lengthy account of that battle too for use in later memoirs. In 1981, by agreement with the plaintiff’s lawyers, a sanitised and updated edition was published, incorporating the Ultra signals, which we shall also post on this website. Saturday, January 26, 2002 |

THESE editions are uploaded onto the FPP website primarily as a tool for students and academics. They can be downloaded for reading or study purposes only, and are not to be commercially distributed in any form.

THESE editions are uploaded onto the FPP website primarily as a tool for students and academics. They can be downloaded for reading or study purposes only, and are not to be commercially distributed in any form.

READERS are invited to submit any typographical or other errors they spot to David Irving via email at info@fpp.co.uk. Informed comments and corrections on historical points are also welcomed.

© website Focal Point 2002, book Parforce UK Ltd 2002 and 2009

David Irving’s famous bestseller:

David Irving’s famous bestseller: David Irving recalls something of the history of this book:

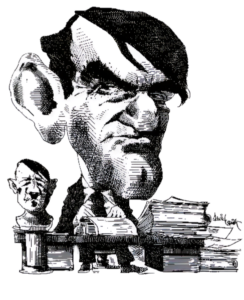

David Irving recalls something of the history of this book: That promised to make 38 separate stories, and using the immense resources of the magazine in funds and manpower I located many of the German submarine and bomber crew members still alive — one of the bomber pilots, Hajo Herrmann, a bearer of the Knight’s Cross (left), became a firm friend and is my brave German lawyer to this day, nearly sixty years after the convoy sailed.

That promised to make 38 separate stories, and using the immense resources of the magazine in funds and manpower I located many of the German submarine and bomber crew members still alive — one of the bomber pilots, Hajo Herrmann, a bearer of the Knight’s Cross (left), became a firm friend and is my brave German lawyer to this day, nearly sixty years after the convoy sailed. The Memoirs of Field Marshal Keitel, which struck me as rather meagre) the manuscript was snapped up by Cassell & Co., Mr Churchill’s publishers.

The Memoirs of Field Marshal Keitel, which struck me as rather meagre) the manuscript was snapped up by Cassell & Co., Mr Churchill’s publishers.