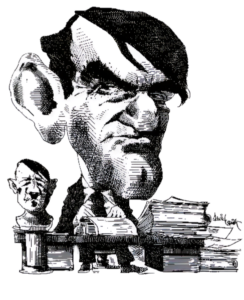

David Irving replies:

David Irving replies:

Hitler’s Table Talk is the product of his lunch- and supper-time conversations in his private circle from 1941 to 1944. The transcripts are genuine. (Ignore the 1945 “transcripts” published by Trevor-Roper in the 1950s as Hitler’s Last Testament — they are fake).

The table talk notes were originally taken by Heinrich Heim, the adjutant of Martin Bormann, who attended these meals at an adjacent table and took notes. (Later Henry Picker took over the job). Afterwards Heim immediately typed up these records, which Bormann signed as accurate.

François Genoud purchased the files of transcripts from Bormann’s widow just after the war, along with the handwritten letters which she and the Reichsleiter had exchanged.

For forty thousand pounds — paid half to Genoud and half to Hitler’s sister Paula — George Weidenfeld, an Austrian Jewish publisher who had emigrated to London, bought the rights and issued an English translation in about 1949.

For forty years or more no German original was published, as Genoud told me that he feared losing the copyright control that he exercised on them. I have seen the original pages, and they are signed by Bormann.

They were expertly, and literately, translated by Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens, though with a few (a very few) odd interpolations of short sentences which don’t exist in the original — the translator evidently felt justified in such insertions, to make the context plain.

Translation is a difficult chore: I have translated four books, including Nikki Lauda‘s memoirs — one can either produce a clinical, wooden, illiterate version, like Richard “Skunky” Evans‘ courtroom translations of Third Reich documents, or one can produce a readable, publishable text which properly conveys the sense and language of the original.

Try translating for publication the Joseph Goebbels diaries — written often in a Berlinese vernacular — without running into trouble with the courts! Louis Lochner succeeded in my view magnificently.

Weidenfeld’s translator also took liberties with translating words like Schrecken, (see facsimile above), which he translated as “rumour” in the sense of “scare-story”. In my own view such translations are acceptable, but they caused a lot of difficulty at the Lipstadt Trial where I found myself accused of manipulating texts and distorting translations (because although I relied on the Weidenfeld translation, I had had access to the original document, and should have known that the actual word was Schrecken).The Table Talks’ content is more important in my view than Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and possibly even more than his Zweites Buch (1928). It is unadulterated Hitler. He expatiates on virtually every subject under the sun, while his generals and private staff sit patiently and listen, or pretend to listen, to the monologues.

Along with Sir Nevile Henderson‘s gripping 1940 book Failure of a Mission, this was one of the first books that I read, as a twelve year old: Table Talk makes for excellent bedtime reading, as each “meal” occupies only two or three pages of print. My original copy, purloined from my twin brother Nicholas, was seized along with the rest of my research library in May 2002.

I have since managed to find a replacement, and I am glad to say that — notwithstanding the perverse judgment of Mr. Justice Gray — Hitler’s Table Talk has recently come back into print, unchanged: Schrecken and all.