International Campaign for Real History

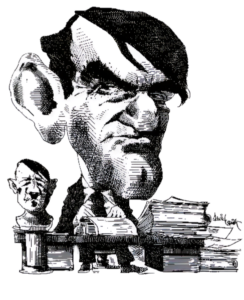

David Irving: Uprising: One

David Irving and the 1956 Revolution The book’s Introduction reveals that Irving had visited Hungary on several occasions. He interviewed, among others, András Hegedüs, Hungary’s Prime Minister at the time when the revolution broke out; (later, after the 1960s, Hegedüs turned against the dictatorship and became an opposition politician and thinker). He also talked to Péter Rényi, who during the 1970s and 1980s was deputy editor of Népszabadság, the Party’s official daily paper; to György Marosán, a former Social Democrat who was, for a number of years after 1956, Kádár’s “strong man”, and who, until his fall from grace in 1962, was seen as Kádár’s rival; and to several politicians active in 1956, including Miklós Vásárhelyi, the press secretary of the Imre Nagy cabinet. In the Introduction, Irving acknowledges his special gratitude to Ervin Hollós, the Kádár regime’s most influential historian on the “counter-revolution”, who was a police lieutenant colonel after 1956, acting as head of the Political Investigation Department of Budapest, and the éminence grise behind the reprisals following the revolution. According to the archives of the Hungarian Foreign Ministry, David Irving made contact with the London Embassy of the Hungarian People’s Republic in 1973. We learn of this first contact from a document filed later, in 1974. According to this, Irving offered to “come out with a book that challenged the fashionable western interpretation.” He promised to draw an “objective” picture of 1956, one that also included the elements of the official Hungarian view; in addition, he also offered to “hand over the photocopies of documents related to the events of 1956, held in British, West German and US archives.” The authorities concerned were of the opinion that Irving’s offer was worth considering. After conferring with the HSWP (Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party) Agitation and Propaganda Department, the Foreign Ministry issued the necessary visa to Irving, who on his first visit to Hungary in 1973 met Péter Rényi, the hardliner deputy editor of Népszabadság. To inspire trust, Irving declared that he had never read the Western publications on 1956, because he did not want to be influenced by them. Rényi, by contrast, was of the opinion that Irving

The report mentions that Rényi had tried to dissuade Irving from the project. During the following years there was internal discussion on the usefulness and actuality of Irving’s offer. However, contacts with Irving were not severed, and the direct negotiations were conducted by the Hungarian Embassy in London. In a letter dated October 9, 1974, Ambassador Vencel Házi came out in favour of supporting Irving’s project. He pointed out that “books of right-wing conception” were coming out one after the other, bearing in mind first and foremost William Shawcross’s Kádár biography. Published in 1973, Shawcross’s book irritated the Hungarians to such a degree that they tried to stop its publication by applying pressure on the Foreign Office’s Press Department. On that basis, therefore, Vencel Házi recommended the following course of action:

Jenö Randé, head of the Foreign Ministry’s Press Department, did not share the Ambassador’s opinion. In a letter written on November 4, 1974 he argued:

The Foreign Ministry’s apparatus was firmly of the opinion that there was nothing to be gained from keeping the subject of 1956 open. It would impede Hungary’s efforts to improve relations with the West, and would only limit the country’s manoeuvring space; in addition, keeping the discourse on 1956 open would only serve the interests of those who would like to continue keeping Kádár’s Hungary in a political quarantine. The documents fail to mention the name of the person who made the decision at the top level to support Irving regardless of all these objections. Tamás Pálos, the deputy head of the Agitation and Propaganda Department, played an important role in tipping the scale. In November 1974 Pálos wrote to Mihály Kornidesz, the head of the HSWP’s Scientific, Public Education and Cultural Department. He argued:

Naturally, Pálos was fully aware of the possible risks and counter-arguments. On January 6, 1975, just one day before the final decision, he wrote to Károly Grósz, the Department’s newly appointed head (Károly Grósz later became Kádár’s successor, appointed as Prime Minister in 1988 and serving as the Party’s last First Secretary in 1988-89):

On the following day, the Agitation and Propaganda Committee endorsed the proposal of the Agitation and Propaganda Department:

On the other hand, the committee’s resolution makes it clear that “we shall not lend any financial support to Irving’s endeavour.” Still on this same day, Pálos sent a communiqué to Jenö Randé at the Foreign Ministry’s Press Department:

Irving was given the green light. According to Jenö Randé’s report, Irving arrived in Hungary for his second visit on March 9, 1975. This time he stayed only for a few days in order to meet his assigned consultant, Ervin Hollós. Since Hollós was busy, they only met once, on March 12, for dinner at the Hotel Gellért. The Foreign Ministry’s interpreter, Erika László, reported that Irving had failed to make a good impression on Hollós. Irving asked Hollós to compile some sort of a list of source documents for his next, longer, visit in the autumn. The report also mentions Irving stating that “should the Hungarians fail to provide material for his topic, he would probably drop the idea of writing the book altogether.” There is a hiatus in the documents after this. We know that Irving returned to Hungary on numerous occasions between 1975 and 1979, and conducted several interviews during his stays. He also visited Moscow, where he had a chance to talk to General [Pavel] Batov, who had commanded the strategically very important Sub-Carpathian Military Region during the revolution. The documents held in Hungarian archives, however, shed no light on these trips. We can once again pick up the thread in the summer of 1978. We find Rezsö Bányász, at the head of the Foreign Ministry’s Press Department at the time, the man who subsequently became the government spokesman. In a letter dated July 29, 1978, he advised the Agitation and Propaganda Department to sever relations with Irving. Bányász believed that Irving was not a serious writer, and he was not familiar with Hungarian history either. On top of that, Bányász was already aware of the media response generated by his book on Hitler — “he wrote a book that took a favourable view of Hitler” — and he also warned of Irving’s intention to meet disreputable characters (presumably he was thinking of members of the opposition in 1956). But Pálos still stuck to his earlier decision, pointing out in his brief reply that “in the matter of the British historian David Irving, we continue to stand by our decision made in January 1975.” Therefore, they continued maintaining contact with Irving. In the autumn of 1978 Irving once again applied for a visa. The London Embassy’s report to the Foreign Ministry noted that

However, the Foreign Ministry’s evaluation on the following day still showed some vacillation:

Rezsö Bányász summed up what was to be done as follows:

It was decided, therefore, that for the time being they would not sever contacts with Irving. The only explanation for this is that they were still hoping to get hold of classified western intelligence. Irving himself felt that the trust in him was dwindling away. In a letter sent through the press attaché in London, he once again asked for an interview with Kádár:

Irving made a definite promise that on this visit he would bring the CIA materials in question. With the letter he also enclosed a document that he had found in Radio Free Europe’s archive in Munich. This document is Item 7487/56 (dated July 28, 1956, ten days after Rákosi’s removal, describing how Kádár had been tortured in prison. The London Ambassador János J. Lörincz warned against complying with the request. In his opinion the interview would merely have served to legitimize statements made in the book. As to the book itself, he set little store by it: “there might be some favourable parts on the role of the Western organizations, but rather sensationalist.” And then the recurring dilemma: “For us the topic of 1956 is inconvenient, regardless of the tone.” Nevertheless, the Hungarians could not bear losing the promised documents. Overturning his earlier, decidedly negative view, Rezsö Bányász wrote to Ervin Hollós on March 27, 1979, addressed to the Scientific Socialism Department of the Budapest Technical University.

In August 1979 Irving once again applied for a visa. In his cable he raised the question of the interview. By that time Tamás Pálos’s response, too, was negative.

He got his visa in the end. In September 1979 Irving returned to Hungary once again. Although he did not get to see Kádár, he did meet Ervin Hollós, and he handed him copies of the telegrams that the Budapest Legation of the United States had sent between October 23 and November 4, 1956. In connection with the documents, Rezsö Bányász, the head of the Foreign Ministry’s Press Department, quarreled with Ervin Hollós. Bányász was resentful that Hollós had failed to hand over the documents to the Foreign Ministry. Hollós retorted that he naturally handed in the documents, but he did so to the appropriate Hungarian official body. Without a shadow of a doubt he was alluding to the Ministry of Interior.

This site is maintained by Hungary.Network. http://www.hungary.com/

|

| © Focal Point 2002 |